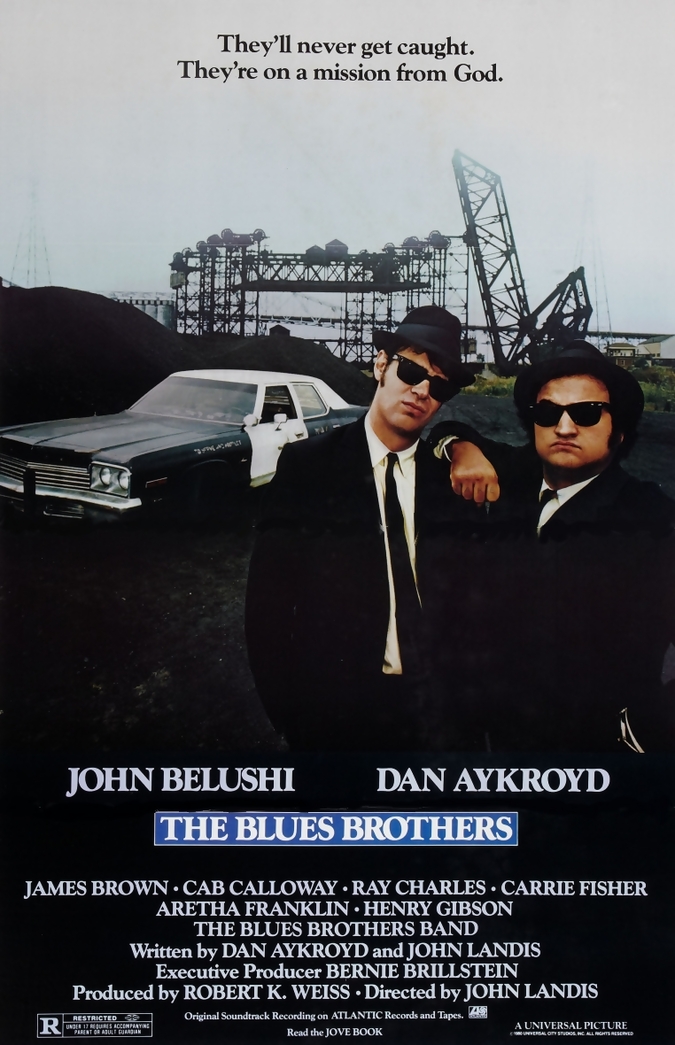

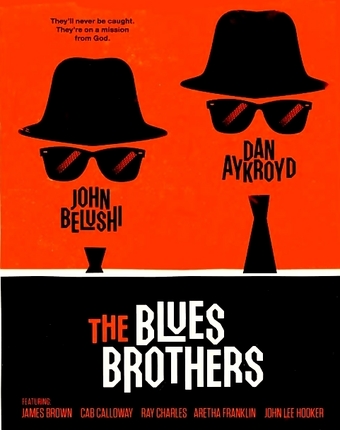

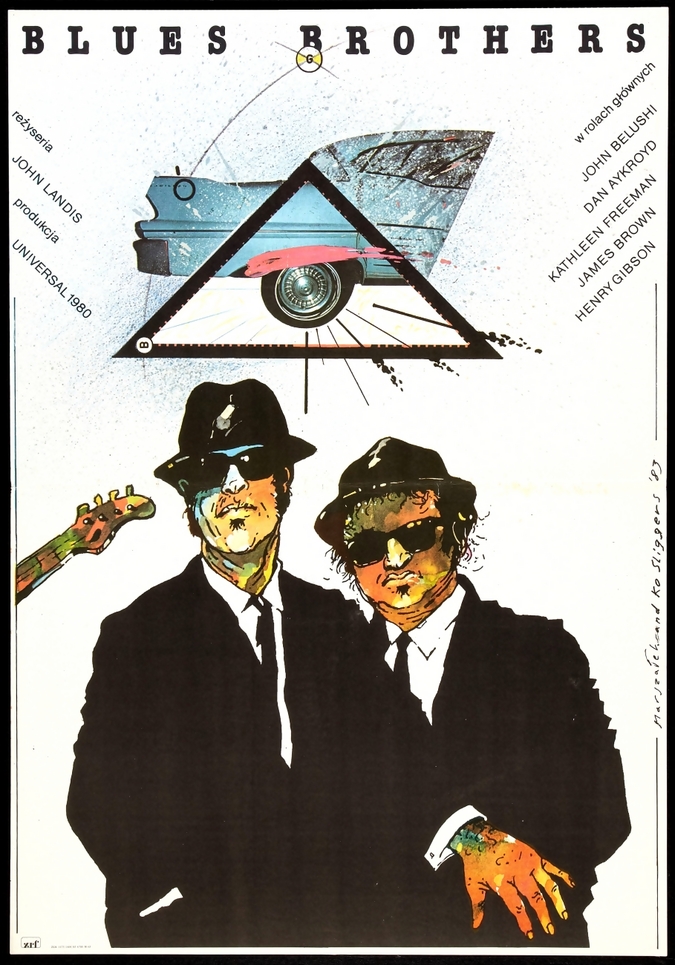

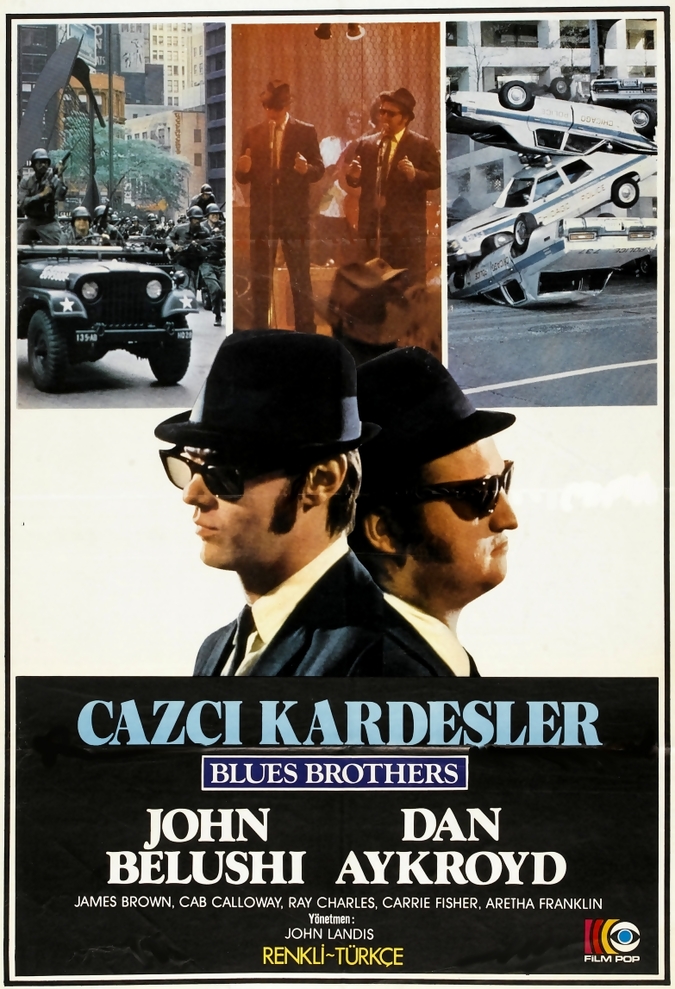

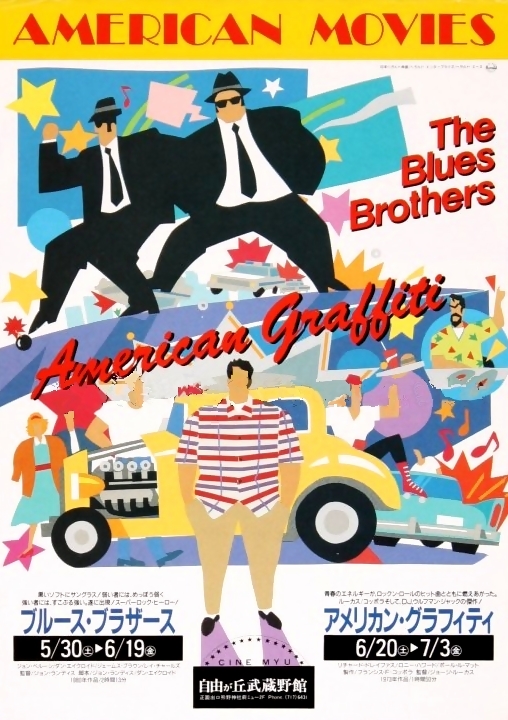

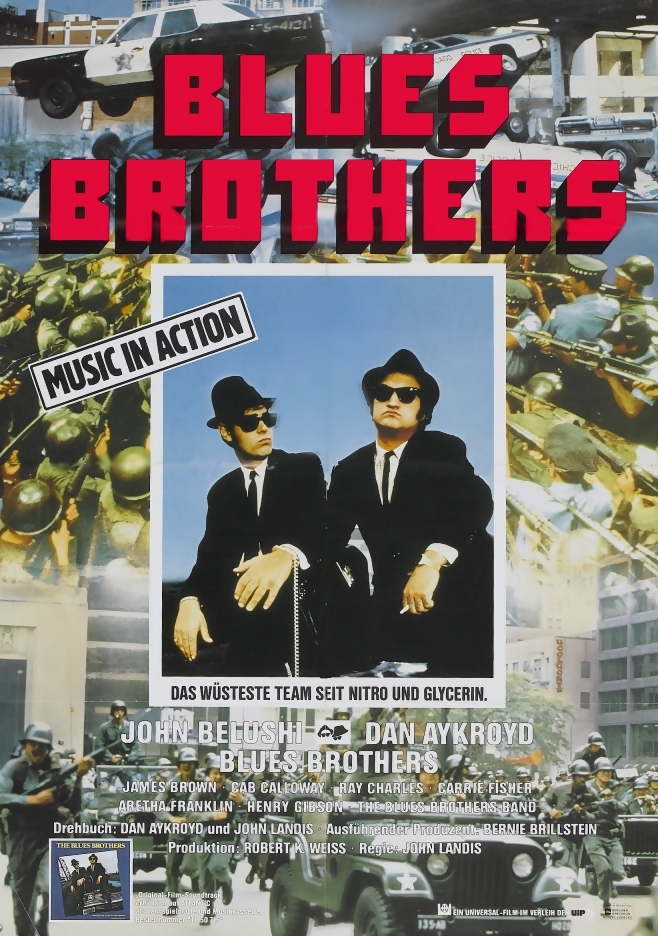

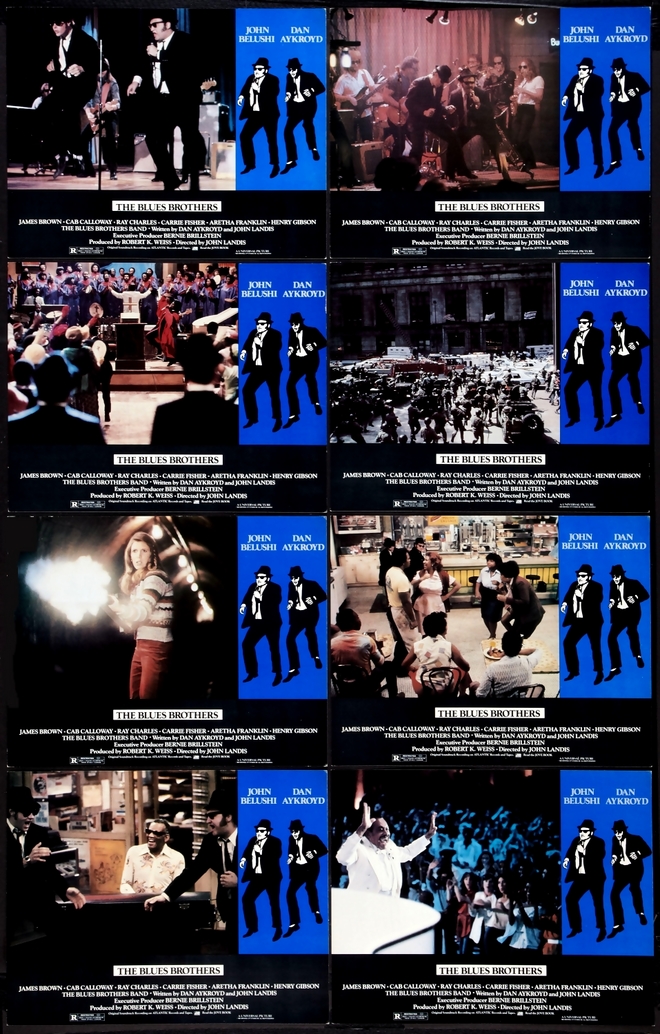

The Blues Brothers is a large-scale musical comedy, and marked the movie debut of Jake and Elwood Blues (John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd). The film has become a legend with movie fans and is highly popular in music circles to this day. Belushi and Aykroyd, who created the Blues Brothers, star in the Universal Picture with James Brown, Cab Calloway, Ray Charles, Carrie Fisher, Aretha Franklin, Henry Gibson, and The Blues Brothers Band: Steve Cropper, Donald “Duck” Dunn, Murphy Dunne, Willie Hall, Tom Malone, Lou Marini, Matt Murphy, and Alan Rubin, with John Landis directing and Robert K. Weiss as producer. The executive producer is Bernie Brillstein, and this was his motion picture debut. The original screenplay is by Aykroyd and Landis, and is Aykroyd’s screen-writing debut. The supporting cast features John Candy, the great blues musician John Lee Hooker (backed by Big Walter Horton; Pinetop Perkins; Willie “Big Eyes” Smith; Guitar Junior, a.k.a. Luther Johnson; and Fuzz Jones), Steve Lawrence, Twiggy, Kathleen Freeman, Muppet performer Frank Oz playing a human being, Charles Napier, Jeff Morris, Steven Williams, Armand Cerami, and James Cleveland’s Southern California Community Choir. The Blues Brothers is a large-scale musical comedy, and marked the movie debut of Jake and Elwood Blues (John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd). The film has become a legend with movie fans and is highly popular in music circles to this day. Belushi and Aykroyd, who created the Blues Brothers, star in the Universal Picture with James Brown, Cab Calloway, Ray Charles, Carrie Fisher, Aretha Franklin, Henry Gibson, and The Blues Brothers Band: Steve Cropper, Donald “Duck” Dunn, Murphy Dunne, Willie Hall, Tom Malone, Lou Marini, Matt Murphy, and Alan Rubin, with John Landis directing and Robert K. Weiss as producer. The executive producer is Bernie Brillstein, and this was his motion picture debut. The original screenplay is by Aykroyd and Landis, and is Aykroyd’s screen-writing debut. The supporting cast features John Candy, the great blues musician John Lee Hooker (backed by Big Walter Horton; Pinetop Perkins; Willie “Big Eyes” Smith; Guitar Junior, a.k.a. Luther Johnson; and Fuzz Jones), Steve Lawrence, Twiggy, Kathleen Freeman, Muppet performer Frank Oz playing a human being, Charles Napier, Jeff Morris, Steven Williams, Armand Cerami, and James Cleveland’s Southern California Community Choir.

Production Production

The Blues Brothers is a unique blend of musical comedy with outrageous humor, location realism, and spectacular action. Says director John Landis, ‘The Blues Brothers’ is a true musical comedy. People burst into song and dance just as they do in the original American form invented on Broadway and glorified in Hollywood. But the story, the musical numbers, and the comedy all have a very realistic look. The film is designed for music and is very stylized.” Dan Aykroyd, who wrote the original screenplay with Landis, described it as “a Christian crusader’s tale, a simple story with no hidden meanings or messages. It was written in a spirit of freedom and celebration. It’s the story of two hoodlums who want to go straight and get redeemed. But they just don’t have it together and they keep getting into bigger and bigger trouble.” “Jake and Elwood are on a genuine crusade,” says Landis. “It’s not the Holy Grail they’re after, it’s 5,000 bucks. But their quest is for equally good reasons. They’re good and sympathetic people. To me, that’s the strength of the movie. The audience must like the characters.”

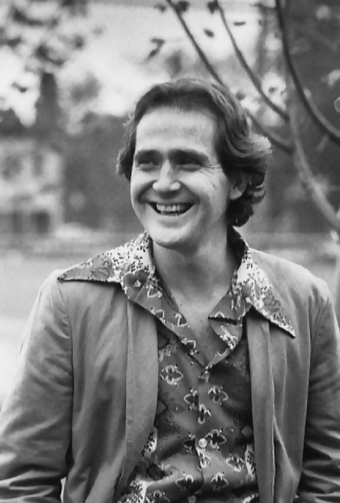

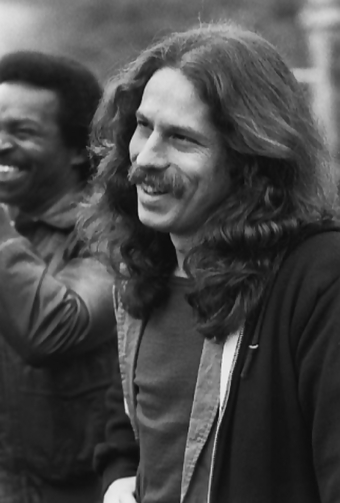

It was just “fooling around, for fun” when best friends Belushi and Aykroyd first created Jake and Elwood. They developed the act for friends, at local clubs, and on cross-country trips. They then performed on a few Saturday Night Live warm ups and appeared as The Blues Brothers twice on the show itself in 1977-78. Aykroyd later said in an interview with Rolling Stone, “John was into rock and roll and heavy metal rock, I was more into blues. We turned each other on to our favorite songs and musicians. Then he assembled the band while I wrote the saga.” Belushi, said Landis years later, “was the ultimate rock fan, a real groupie. He played drums when he was eight, and had his own band in high school. If he hadn’t become an actor first, he would certainly have been a musician. John and Danny are very knowledgeable about music, not dilettantes.They understand who black musicians are and what they’re doing, and they wanted to honor and be a part of that great tradition.” The idea for a Blues Brothers movie originated with Aykroyd and was in development long before the first album. In June of 1978, The Blues Brothers opened for Steve Martin at the Universal Amphitheater. No one expected the thunderous reception The Blues Brothers got during this engagement, which band member Steve Cropper later called “the nine most exciting days of my musical life.”

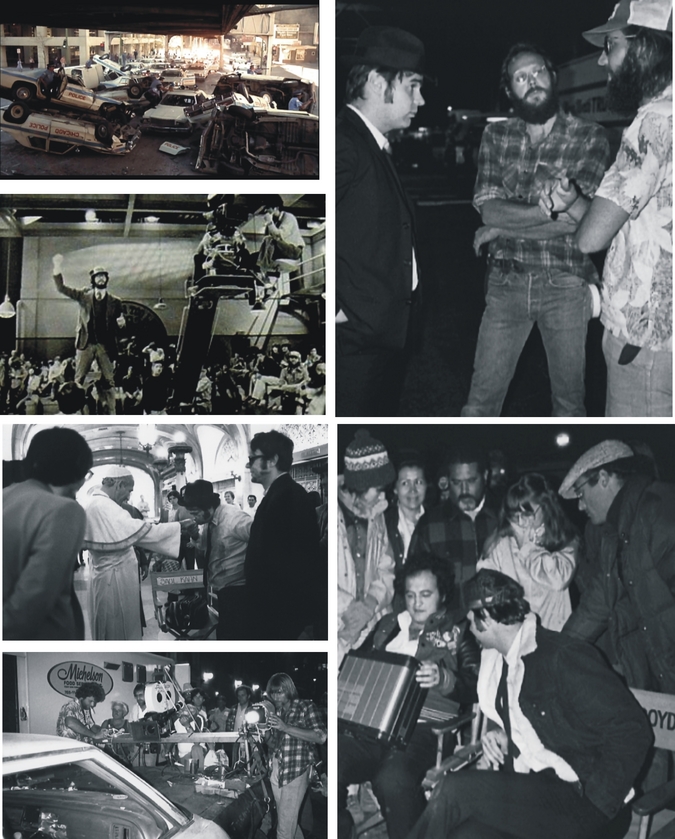

Various production photos (left click to enlarge)The album, recorded during this engagement, was released in late 1978 and started its climb to double Platinum status. It hit number one on the national charts and yielded the hit single, “Soul Man.” The Blues Brothers started filming in summer of 1979, and in 1980 the album received three Grammy nominations. John Belushi said, “Jake is into music, drinking, and sliding through life. His craziness confuses Elwood. Elwood is religious, a bookworm, and a motor head. He takes care of the details. Jake’s lies upset Elwood, and Elwood’s driving makes Jake nervous. “Elwood looks up to Jake and listens to him. That’s how they get into a lot of their trouble, and Elwood usually gets them out. Jake thinks he’s smarter than Elwood, and Elwood thinks he’s dumber than Jake, but it’s really the opposite. Deep down, they love each other, and know they can count on each other, but they barely get along.” “It’s a tenuous relationship,” agreed Aykroyd. “They’re like a couple that’s been together too long. There’s always a sibling tension present.”

Various production photos (left click to enlarge)The album, recorded during this engagement, was released in late 1978 and started its climb to double Platinum status. It hit number one on the national charts and yielded the hit single, “Soul Man.” The Blues Brothers started filming in summer of 1979, and in 1980 the album received three Grammy nominations. John Belushi said, “Jake is into music, drinking, and sliding through life. His craziness confuses Elwood. Elwood is religious, a bookworm, and a motor head. He takes care of the details. Jake’s lies upset Elwood, and Elwood’s driving makes Jake nervous. “Elwood looks up to Jake and listens to him. That’s how they get into a lot of their trouble, and Elwood usually gets them out. Jake thinks he’s smarter than Elwood, and Elwood thinks he’s dumber than Jake, but it’s really the opposite. Deep down, they love each other, and know they can count on each other, but they barely get along.” “It’s a tenuous relationship,” agreed Aykroyd. “They’re like a couple that’s been together too long. There’s always a sibling tension present.”

The Blues Brothers, observed Landis, “are not a comedy team per se, like Laurel and Hardy or Abbott and Costello. They’re individual characters brought to life by actors giving fine performances. “The Blues Brothers spring directly from John and Danny’s passion for music.” Belushi called the film “a tribute to black American music.” The score showcases music of the past four decades and some of its greatest performers. They all play characters who are integral to the story. The score contains blues, rock and roll, soul, and rhythm and blues, as well as some country-western, pop, Latin, and classical. The Blues Brothers, observed Landis, “are not a comedy team per se, like Laurel and Hardy or Abbott and Costello. They’re individual characters brought to life by actors giving fine performances. “The Blues Brothers spring directly from John and Danny’s passion for music.” Belushi called the film “a tribute to black American music.” The score showcases music of the past four decades and some of its greatest performers. They all play characters who are integral to the story. The score contains blues, rock and roll, soul, and rhythm and blues, as well as some country-western, pop, Latin, and classical.

To bring The Blues Brothers to the screen, the filmmakers spent three-and-a-half months on location in Chicago, where Jake and Elwood’s story is set. Said producer Weiss: “We received unprecedented cooperation from the city of Chicago, the state of Illinois, and local talent and crews. Rarely have I seen or heard of a city making so many locations available to one film production. As a result, we feel that our movie highlights the rich atmosphere of this unique metropolis better than it has ever been seen on the screen before.” Said Landis: “We were allowed to film things on a scope and scale that have rarely been done before in the center of a large city.” The first day’s filming had 76 movie police cars zooming over Chicago’s bridges and under the post office building in pursuit of The Blues Brothers. The action scenes were filmed on Sundays and holidays, when the center of the city was almost entirely vacant and people would not be disturbed. By Monday, all the debris was cleaned away. The Daley Plaza invasion was done over the Labor Day weekend. The Blues Brothers location filming was a triumphant homecoming for John Belushi, who was born and raised in “Sweet Hortie Chicago.” He was a graduate of Wheaton Central High and alumnus of the Second City comedy troupe. He called Chicago “the most creative city in the U.S.,” a place where “I feel I’m part of the community.” While filming in Chicago, Belushi revisited Second City and its influential director, Del Close, who taught Belushi improvisation. Aykroyd, a veteran of Second City’s Toronto branch, had performed briefly in the Chicago company and also paid it a visit.

On Location On Location

The location filming was also a return of the native for Landis, who was born in Chicago. His family moved to Los Angeles when he was four months old. Landis welcomed the chance to revisit Bushman the gorilla, who is now stuffed at the Chicago Museum of Natural History, and Otto the Gorilla, who is alive and well at the Lincoln Park Zoo. Producer Robert K. Weiss had visited Chicago before while studying Film and TV Production at Southern Illinois University. The Blues Brothers is a very American movie,” said Landis. “You see a remarkably diverse spectrum of American life in this film.” The locations included colorful Maxwell Street, steel mills, a suburban shopping mall, the Cook County Building, various expressways and bridges, interiors and exteriors of Joliet Prison, the front of a high-class downtown restaurant, the exterior of the South Shore Country Club, and Daley Plaza. There the famous enigmatic Picasso sculpture seemed to look on in amazement as the film crew launched a full-scale invasion of the business and government center. The attack on Daley Plaza featured dozens of stunt people, six camera crews, 300 crowd extras, 100 extras costumed as police, 300 National Guardsmen costumed as soldiers, a four-man SWAT team repelling down the Cook County Building, seven mounted police, three Sherman M4 tanks, five fire engines, and two Bell Jet Ranger helicopters.

Because the camera helicopter was hit by a truck the night before, the camera crew got high-angle shots from the square’s Anglican church, the world’s tallest church. Jake and Elwood travel through this panorama of the Midwest in a 1974 Dodge Monaco 440 known as “The Bluesmobile.” The film “co-stars” this battered-but-magical, former Mount Prospect police car and features an accelerating series of automobile chases and stunts. “The Bluesmobile is almost a character in the film,” commented producer Weiss for The Hollywood Reporter, “It moves across the country like a land shark.” The story’s action includes the leaping of an opening swing bridge over the river; the slam-bang, three-car demolition of an indoor shopping mall; a 106-mile, all-night pursuit from a small town into the center of Chicago; multi-car chases and a pileup under the el tracks; a mid-air back flip by the elusive Bluesmobile; a police car flying into the side of a moving semi; an out-of-control Winnebago crashing through a warehouse and flying into a river; the dizzying 1200-foot fall of a car into the heart of metropolitan Chicago; a high-speed chase through the narrow underground tunnels of Lower Wacker Drive; and the climactic assault on Daley Plaza, in which The Bluesmobile crashes through the lobby of the Richard J. Daley Building. To accomplish their panoramic demolition derby, the filmmakers acquired 60 Chicago cars which the full-time special effects crews continually reconditioned and recycled into new scenes, often overnight. In addition, there were 13 Bluesmobiles, each specially customized for various maneuvers. One had separate brakes on each tire for unprecedented control in spins and other stunts. Another was built over a month’s time to disintegrate at the last automotive moment of Jake and Elwood’s exhausting odyssey.

Behind the scenes on location photosThe shopping mall which was demolished by The Bluesmobile and two pursuing Illinois State police cars was the Dixie Mall in Harvey, Illinois. Production designer John J. Lloyd was delighted to discover the over-100,000-square-foot mall completely empty. He rebuilt 32 stores of the indoor plaza into a veritable shrine of American consumerism, perhaps the largest location set ever built. Then the filmmakers ravaged the place. Later the crew returned it to its pre-“Blues” condition. The rapid-fire demolition, less than three minutes on screen, took months to prepare, five days to film, and involved dozens of stunt people. The cars traveled at high speeds in the mall’s confined spaces, crashing real glass and scattering real merchandise. One of the ISP cars was driven by Landis (with a mustache) with pop singer Stephen Bishop, as state troopers. Said Landis, a former stunt man: “It was like giving a kid a sledge hammer.” An explosion sent a mock phone booth 200 feet high in a gas station near O’Hare airport.

Behind the scenes on location photosThe shopping mall which was demolished by The Bluesmobile and two pursuing Illinois State police cars was the Dixie Mall in Harvey, Illinois. Production designer John J. Lloyd was delighted to discover the over-100,000-square-foot mall completely empty. He rebuilt 32 stores of the indoor plaza into a veritable shrine of American consumerism, perhaps the largest location set ever built. Then the filmmakers ravaged the place. Later the crew returned it to its pre-“Blues” condition. The rapid-fire demolition, less than three minutes on screen, took months to prepare, five days to film, and involved dozens of stunt people. The cars traveled at high speeds in the mall’s confined spaces, crashing real glass and scattering real merchandise. One of the ISP cars was driven by Landis (with a mustache) with pop singer Stephen Bishop, as state troopers. Said Landis, a former stunt man: “It was like giving a kid a sledge hammer.” An explosion sent a mock phone booth 200 feet high in a gas station near O’Hare airport.

Scenes such as these occasionally necessitated closing off traffic briefly on a few interstate highways and, on the first day’s filming, the Kennedy Expressway. For the pileup under the highway, cars were made to flip in long leaps by launching them off innovatively constructed, greased pipe-ramps made of rolled tubular steel, welded together. In other chase scenes, specially designed wooden ramps gave the car-jumps added power and height. Landis’ perfectionism in structuring these sight gags demanded an extraordinarily high level of accuracy in the execution of large-scale stunts.

While filming, Universal prepared a grand merchandising planAll but one of the spectacular effects in the car stunts were achieved by actually doing them on camera and on location, instead of relying on optical effects or doing them in the studio. Good examples are the pileup under the el, the back-flip, and the ISP car that flies into the side of a moving truck which keeps rolling down the highway. A better one is the amazing plummet of the Nazis’ car off an uncompleted freeway and down, down, down into a Chicago street. The horrendous fall was accomplished by helicopter-lifting a Pinto 1200 feet over the heart of the city and dropping it into a vacant lot. To perform this extraordinary operation, the filmmakers had to obtain permission and close supervision from the Federal Aviation Administration, and do a test drop outside the city to prove they could safely predict the landing point. In the filmed drop, the car landed ten feet from its projected target and crunched to a height of 18 inches. The lead-in to this shot, the Nazis chase, was filmed on an uncompleted freeway in Milwaukee. In the ferocious chase through Lower Wacker Drive, as many cars were going up to 90 miles per hour, to maintain safety they hired dozens of policemen and 62 production assistants to prevent unaware drivers and pedestrians from entering the area.

While filming, Universal prepared a grand merchandising planAll but one of the spectacular effects in the car stunts were achieved by actually doing them on camera and on location, instead of relying on optical effects or doing them in the studio. Good examples are the pileup under the el, the back-flip, and the ISP car that flies into the side of a moving truck which keeps rolling down the highway. A better one is the amazing plummet of the Nazis’ car off an uncompleted freeway and down, down, down into a Chicago street. The horrendous fall was accomplished by helicopter-lifting a Pinto 1200 feet over the heart of the city and dropping it into a vacant lot. To perform this extraordinary operation, the filmmakers had to obtain permission and close supervision from the Federal Aviation Administration, and do a test drop outside the city to prove they could safely predict the landing point. In the filmed drop, the car landed ten feet from its projected target and crunched to a height of 18 inches. The lead-in to this shot, the Nazis chase, was filmed on an uncompleted freeway in Milwaukee. In the ferocious chase through Lower Wacker Drive, as many cars were going up to 90 miles per hour, to maintain safety they hired dozens of policemen and 62 production assistants to prevent unaware drivers and pedestrians from entering the area.

There’s no better place for a stuntman to study his next sceneFor the crash through the windows of the Daley Building, real panes of glass were replaced by more breakable thin ones. The movie makers spent three days inside Joliet Prison filming Jake’s release. With real prisoners as extras, they worked in a cell block, the yard, the sally-port, and a quartermaster’s building. To depict Jake’s dramatic emergence from the pen, the film unit arranged for the opening of a gate that hadn’t been used in decades. The color and clamor of Maxwell Street were captured during two bustling days in the famous flea market area, a mecca of blues and jazz music. In this scene, the redecorated front of popular Nate’s Kosher Delicatessen doubled as the exterior of Aretha Franklin’s Soul Food. The inside of the funky restaurant was a set on a Universal soundstage. Similarly, the Blues Brothers’ screeching arrival at Chez Paul was filmed outside the elegant Chicago restaurant, while the interior was a studio set.

There’s no better place for a stuntman to study his next sceneFor the crash through the windows of the Daley Building, real panes of glass were replaced by more breakable thin ones. The movie makers spent three days inside Joliet Prison filming Jake’s release. With real prisoners as extras, they worked in a cell block, the yard, the sally-port, and a quartermaster’s building. To depict Jake’s dramatic emergence from the pen, the film unit arranged for the opening of a gate that hadn’t been used in decades. The color and clamor of Maxwell Street were captured during two bustling days in the famous flea market area, a mecca of blues and jazz music. In this scene, the redecorated front of popular Nate’s Kosher Delicatessen doubled as the exterior of Aretha Franklin’s Soul Food. The inside of the funky restaurant was a set on a Universal soundstage. Similarly, the Blues Brothers’ screeching arrival at Chez Paul was filmed outside the elegant Chicago restaurant, while the interior was a studio set.

|

|

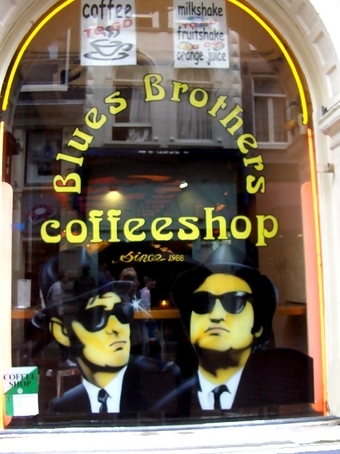

| Famous coffee shop in Amsterdam |

“On the cover of the Rolling Stone” |

The exteriors of the concert sequence were filmed in Chicago at the restored and redecorated front facade of the defunct South Shore Country Club. The interiors were done at the Hollywood Palladium. The interior audience was recruited through an announcement over Los Angeles’ KMET Radio. To help the audience cope with the inevitable boredom of four days’ filming, Belushi and Aykroyd performed for them off-camera. The enthusiasm of the crowd did not have to be faked. In addition to seeing The Blues Brothers in person, they got to discover a star from another generation, Cab Calloway. They responded to his “Hi De Ho’s” with the same delight as the hep cats used to do and gave Calloway a spontaneous standing ovation. Other Chicago locations include Jackson Park (scene of the Nazi’s rally) and Lake Wauconda (Lake Wazapamani). Among other sets constructed in Chicago were the front of the orphanage and the interior of the Nazi headquarters at the historic Essanay Studios, where many silent film stars once worked. Pre-recording of the musical numbers was done in Chicago by Belushi, Aykroyd, the band, Cab Calloway, Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin.

The stunt crewChoreography and Costuming

The stunt crewChoreography and Costuming

The film’s choreography blends theatrical Broadway style, traditional Hollywood numbers, totally cinematic constructions, and concert staging. “I didn’t want to make rules and have a single dancing style,” said Landis, “I wanted to use whatever was right for that part of the film.” Choreographer Carlton Johnson incorporated moves that Belushi and Aykroyd had used in their Blues Brothers concerts and taught them many new steps created especially for them. The church number features 36 dancers recruited from the Los Angeles area. The 41 professional dancers on the street outside Ray’s Music Exchange were all found in Chicago. The rest of the crowd is made up of hired extras and energetic crew members. The people seen twisting on the el platform are actual train passengers who decided to join in the fun. The black suits and hat worn by Jake and Elwood were derived from jazz album covers of the Fifties and were originally worn by John Lee Hooker. This getup was intended to make musicians look like businessmen and thus avoid the attention of the police. In creating The Blues Brothers, John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd added the (Ray Ban) sunglasses and the (Timex) digital watches. The film’s costume designer, Deborah Nadoolman, made thirty subtly different versions of the hats and mohair suits and five for Cab Calloway, to accommodate the actors’ physical and character differences and the demands of the movie, including stunts and musical numbers.

|

|

| Henry Gibson authentic costuming |

Carrie Fisher was costumed for “the girl next door” |

The wardrobe provided for Carrie Fisher by Nadoolman was intended to typify middle America and was obtained entirely from Sears. “The Mystery Woman’s” outfits are all polyester, embellished by an anklet, vinyl shoes, a Timex watch, a gold-plated cross, hoop earrings, pantyhose, and the camel-colored, vinyl shoulder bag she sports while firing the flame thrower. Her vested peasant dress echoed her Romanian background, and the sweater she wears during her family-revenge speech is a garment knitted by her mother. The hand that turns the page of the military weapons manual and sets off the remote-control bomb has long artificial fingernails, beautifully manicured. Cab Calloway’s white tuxedo is an almost-exact replica of the white tuxes he wore in the Thirties and Forties, on stage and in films.It was made from vintage gabardine and featured silk vest and lapels with antique rhinestone buttons and a fresh gardenia. The robes worn by James Brown and the choir in the church are purple velvet and hot-pink crepe, with pink embroidered crosses on Brown’s velvet cowl. Nadoolman had them produced at a south Chicago establishment that makes garments for local churches and choirs. Henry Gibson’s Nazi uniform was a classic pre-war brown shirt outfit of the kind actually worn by current members of American Nazi parties.

James Brown costume on display in HollywoodTo find Aretha Franklin’s authentic waitress uniform, as well as the colorful clothes for the Baptist congregation, the Maxwell Street throng, and the dancers and extras outside Ray’s music store, Nadoolman foraged through Chicago thrift shops. Franklin’s rust sweater was a man’s garment obtained (on sale) from Marshall Fields’ basement. In the colorful crowd scenes, Nadoolman exercised a fastidious attention to the arrangement and interplay of color. She designed the snazzy western getups of Tucker McElroy and The Good Ole Boys. McElroy wore an adaptation of the John Wayne bib-front shirt in tan and rust with concha buttons and sterling silver collar tips, plus brown pants with rust piping, white patent leather belt with a large sterling silver buckle, and lizard cowboy boots. His band sported the same pants and belts with rust and beige, checkered flannel shirts, and leather boots. As Jake’s parole officer, John Candy wears all polyester outfits with what is known in the costume trade as “a full Cleveland,” white patent leather shoes and belt. On the nun’s habit worn by Kathleen Freeman, the wimpel was the one worn by Loretta Young in Come To The Stable. In Daley Plaza, Nadoolman and her staff dressed up to 700 extras each day.

James Brown costume on display in HollywoodTo find Aretha Franklin’s authentic waitress uniform, as well as the colorful clothes for the Baptist congregation, the Maxwell Street throng, and the dancers and extras outside Ray’s music store, Nadoolman foraged through Chicago thrift shops. Franklin’s rust sweater was a man’s garment obtained (on sale) from Marshall Fields’ basement. In the colorful crowd scenes, Nadoolman exercised a fastidious attention to the arrangement and interplay of color. She designed the snazzy western getups of Tucker McElroy and The Good Ole Boys. McElroy wore an adaptation of the John Wayne bib-front shirt in tan and rust with concha buttons and sterling silver collar tips, plus brown pants with rust piping, white patent leather belt with a large sterling silver buckle, and lizard cowboy boots. His band sported the same pants and belts with rust and beige, checkered flannel shirts, and leather boots. As Jake’s parole officer, John Candy wears all polyester outfits with what is known in the costume trade as “a full Cleveland,” white patent leather shoes and belt. On the nun’s habit worn by Kathleen Freeman, the wimpel was the one worn by Loretta Young in Come To The Stable. In Daley Plaza, Nadoolman and her staff dressed up to 700 extras each day.

|

|

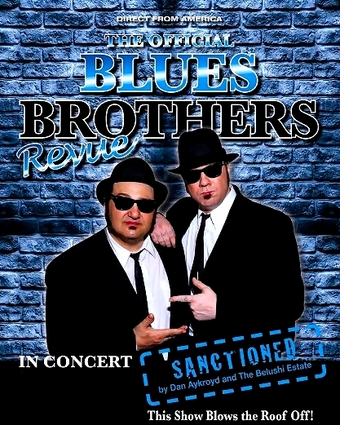

| Aykroyd- sanctioned concert toured the nation and Europe |

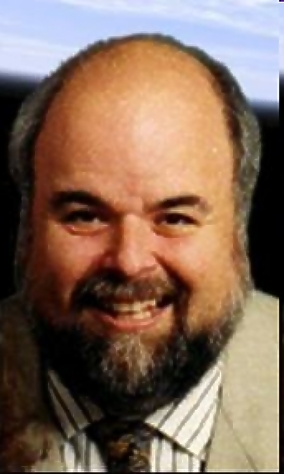

Unused poster art |

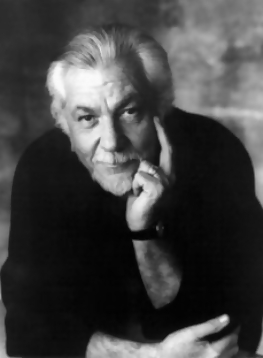

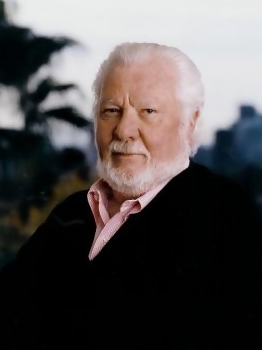

Bernie Brillstein, Executive Producer

Born and raised in New York City, Brillstein attended New York University and started his show business career at the William Morris agency where he was an agent for nine years. Bernie Brillstein has had a highly successful career in all areas of show business as a manager, packager, and career consultant. He made his motion picture debut as Executive Producer of “The Blues Brothers.” Brillstein was also the Executive Producer of the Warner Brothers comedy feature Up The Academy. In television he was the Executive Producer of The Ben Vereen Show and The Burns and Schreiber Show. As head of The Brillstein Company, he represented and guided the careers of John Belushi, Dan Aykroyd, Gilda Radner, Don Novello, Jim Henson (creator of The Muppets) , Lome Michaels (creator of Saturday Night Live), and Yongestreet Productions (producers of Hee-Haw). Brillstein had represented Henson for over 21 years and contributed to the packaging of the phenomenally popular The Muppet Show as well as the top-grossing The Muppet Movie. He also participated in the packaging of Saturday Night Live, and Gilda: Live (the Broadway show and movie). Brillstein also helped package one of television’s most successful long-running series, Hee-Haw, as a representative of Yongestreet Productions, which consisted of producers John Aylesworth, Frank Peppiatt, and Nick Vanoff. It was through Brillstein’s association with Belushi and Aykroyd that he was instrumental in the generation of the Universal film, long before the release of The Blues Brothers’ first Platinum album.

|

|

| Bernie Brillstein when the film released |

Bernie Brillstein |

Robert K. Weiss, Producer

Robert K. Weiss, the young producer of The Blues Brothers came to feature film-making from the field of video production. He made his feature film debut by producing Kentucky Fried Movie, the small-budget anthology comedy which was a sleeper hit of 1977. Weiss was Chief Production Executive of Video Systems Network, Inc., a Los Angeles-based videotape production company, when he saw The Kentucky Fried Theater revue and urged its creators to “do something” with their original, mixed-media comedy. Four years later, he produced Kentucky Fried Movie and served as television director of the anthology comedy’s video segments. “The production of this movie was a logical extension of what I had been doing,” said Weiss. His experience in videotape production trained him to deal with lots of actors, many settings, constant change, and fast, short production schedules. Kentucky Fried Movie was made in 23 days, featuring over 110 speaking parts, hundreds of extras and costumes, and dozens of sets and locations. Produced at under one million dollars, the outrageous comedy has grossed over thirty million. The large-scale production of The Blues Brothers blends outrageous humor and traditional musical comedy with location realism and spectacular action. With unprecedented cooperation from the city of Chicago, it was filmed at over 40 locations in and around Chicago, and at Universal Studios in Los Angeles.

|

|

| Robert K. Weiss, Producer: Publicity Still |

Robert K Weiss |

“The Blues Brothers” continues Weiss’ creative association with director John Landis, who directed Kentucky Fried Movie as well as the comedy smash National Lampoon’s Animal House. Robert K. Weiss was born in the Bronx (New York City) where his father was a physician and his mother a high school guidance counselor. Bob attended the Bronx High School of Science and went on to the University of Louisville. To further foster his interests in TV and film production, he transferred to and graduated from Southern Illinois University. He moved to Los Angeles in 197 2 and joined New Worlds Video Systems as Executive Producer. There, he pioneered a unique use of closed-circuit Electronic News Gathering (ENG) techniques, setting up and operating media systems at large events. For a brief period, he returned to Carbondale, Illinois, to become Media and Marking Executive for H&A Enterprises. In one of several successful nightclubs he opened and operated, Weiss introduced male go-go dancers to the country, a distinction that gained the attention of Time magazine and landed him on the national TV news with Walter Cronkite. In 1974, Weiss joined Video Systems Network in Los Angeles. He produced and directed a variety of programs and worked in software design and marketing. His production work included TV pilot projects, commercials, video-training for the Los Angeles Police Department, and a BBC documentary on outer space. He was also a member of the team that set up and operated the International TV Pool Feed from NASA/JPL Mission Control for the Viking Landing on Mars in 1976.

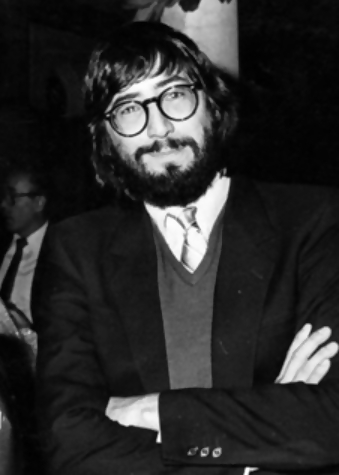

John Landis, Director John Landis, Director

At the age of eight, John Landis saw the fantasy adventure The Seventh Voyage Of Sinbad. “I was enchanted by the movie,” recalled Landis in a 1983 interview with Time. “I went home and asked my mother, ‘Who did that? Luckily for me, she said, ‘The director.'” Today, at the age of 29, Landis is one of the most successful young filmmakers in Hollywood. He is the director and co-writer, of The Blues Brothers. The film, made mainly on locations in and around Chicago, is from an original screenplay by Aykroyd and Landis. Landis previously directed Universal’s college comedy National Lampoon’s Animal House, which was the most popular comedy ever made and one of the ten top-grossing films of all time. This picture was instrumental in elevating John Belushi to film stardom. On college campuses across the country the movie sparked a wave of “toga parties” and related misbehavior.

John Landis was born in Chicago, a third child, and re-located in the Westwood section of Los Angeles when he was four months old. His father, a noted interior decorator, died when John was five, and his mother later married Walter Levine, who works for the city of Los Angeles. John went to Oakwood, a progressive private high school, which he left in the tenth grade. The remainder of his school days were spent in a progressive education program at UCLA, where he taught for over a year. John tried for a job inside a studio, and just as he was becoming convinced that they only went to people with relations in the business, he was hired by 20th-Century-Fox as a mail-boy. He made the most of it, learning about filmmaking by observing the pros at work. He also made a lot of friends, including veteran director Andrew Marton. When Marton was en route to Yugoslavia to direct the second unit of MGM’s big war comedy “Kelly’s Heroes,” John asked for a job and was told they had everyone they needed. That didn’t stop Landis: “I told my mother that I had a job on the movie, spent my life savings for an airplane ticket that got me as far as London, and made my way to Yugoslavia.” Once he was on location, a spot materialized for John as a “go-fer,” the boy who goes for coffee, etc. As the lengthy production rolled on, John was able to assume progressively more important tasks as a production assistant.

|

|

| John Landis on the set |

John Landis publicity still |

John made friends with Clint Eastwood’s stand-in, Jim O’Rourke. When the picture wrapped, Jim landed a job on a film in Almeria, Spain, and asked John to come along and try his luck. “That was the era of the ‘spaghetti western’ and there were productions all over the place,” recalled Landis. He was hired by a British film company as a dialog coach for foreign actors, but stunt work paid better. His first job was falling from a horse. “I’d ridden a little bit at camp when I was 14, and I still ride, badly, but I’m great at falling,” said John. He worked on about 70 films in Europe before he and Jim went home. They looked for work in Hollywood, but their timing was off, the film business was in a serious slump. Unable to find production work, John and Jim started to think in bigger terms, about making their own film. One night, John went to a movie on Hollywood Blvd. which proved fateful: “I love monster movies. When I saw ‘Trog,’ I was so outraged and amused, I went home and immediately started writing ‘Schlock.'” That weekend he completed the original screenplay which affectionately spoofs the whole genre of monster flicks, among other things. Landis and O’Rourke raised the $60,000 needed to produce “Schlock” from friends and relatives. At the age of 21, Landis directed and starred as the monster. He filmed the feature in 15 days on location in the small California town of Agoura, in the San Fernando Valley.

The monster comedy, released in 1972, became a cult classic and in 1973 won the Grand Prix at the 14th Annual Science-Fiction Film Festival in Trieste, Italy, beating out several large-scale and prestigious entries. In 1975, Schlock received the Best Comedy Sequence Award at the Chamrouftee (France) Comedy Film Festival, and Landis won the prize as Best Actor. The innovative and remarkably expressive monster makeup in “Schlock” was the first solo film work of Rick Baker, then 19, who went on to become one of Hollywood’s leading makeup artists. The success of “Schlock” led to Kentucky Fried Movie when David Zucker saw Landis in a promo guest appearance on The Johnny Carson show. He invited John to meet his partners, Jim Abrahams and brother Jerry Zucker. They huddled on weekends for over a year before they and producer Robert K. Weiss made the ten-minute, four-sketch “pilot” film which ultimately sold the feature. Landis and Weiss worked “on spec” on the pilot. After showing it around at the studios, they tested the short film at the Parallax Theaters’ Nuart Cinema in West Los Angeles. Kim Jorgensen, owner of the Parallax chain, saw the explosive audience reaction and offered to help get financing from independent sources. The monster comedy, released in 1972, became a cult classic and in 1973 won the Grand Prix at the 14th Annual Science-Fiction Film Festival in Trieste, Italy, beating out several large-scale and prestigious entries. In 1975, Schlock received the Best Comedy Sequence Award at the Chamrouftee (France) Comedy Film Festival, and Landis won the prize as Best Actor. The innovative and remarkably expressive monster makeup in “Schlock” was the first solo film work of Rick Baker, then 19, who went on to become one of Hollywood’s leading makeup artists. The success of “Schlock” led to Kentucky Fried Movie when David Zucker saw Landis in a promo guest appearance on The Johnny Carson show. He invited John to meet his partners, Jim Abrahams and brother Jerry Zucker. They huddled on weekends for over a year before they and producer Robert K. Weiss made the ten-minute, four-sketch “pilot” film which ultimately sold the feature. Landis and Weiss worked “on spec” on the pilot. After showing it around at the studios, they tested the short film at the Parallax Theaters’ Nuart Cinema in West Los Angeles. Kim Jorgensen, owner of the Parallax chain, saw the explosive audience reaction and offered to help get financing from independent sources.

Backed by a $600,000 budget, Landis and company completed Kentucky Fried Movie in just 23 days. The 22-segment film ranges in style from Oriental karate splendor to taped video shows and black exploitation. Kentucky Fried Movie was a sleeper hit of 1977 and continues to have a cult following. Appearing in surprise cameos were Bill Bixby, Donald Sutherland, Henry Gibson, George Lazenby and recording star Stephen Bishop. About 30 percent of the skits were adapted from the best material presented at the theater. Approximately 70 percent was new material, written directly for the screen, with Landis making sizable contributions. “Kentucky Fried Movie” quickly became what Variety called a “surprise hit.” The film’s outrageous humor and its success with youthful audiences brought Landis to the attention of Universal production executive Sean Daniel, who referred him to “Animal House” producers Matty Simmons and Ivan Reitman. Landis conferred on the script for several months with writers Harold Ramis, Douglas Kenney and Chris Miller before going on location in Eugene, Oregon. Landis made the hilarious film in just 36 days, with an amazing work average of over 30 camera setups a day. He then contributed screenplay material to the James Bond film The Spy who Loved Me. He has also acted in a few films, in addition to “Schlock.” In Steven Spielberg’s “1941,” Landis played a featured role as a military messenger. In “Death Race 2000,” he was killed by auto racer Sylvester Stallone. In Beneath the Planet of the Apes he was a slave to ape Roddy McDowell.

The Blues Brothers Band The Blues Brothers Band

It was during The Blues Brothers’ triumphant nine-day engagement at the Universal Amphitheater in June of 1978 that the first Blues Brothers album, “A Briefcase Full Of Blues,” was recorded. It-went double Platinum (sold over two-and-a-half million units) and in 1980 received three Grammy nominations. All the band members made their film debuts inThe Blues Brothers except Murphy Dunne and Tom Malone. Six of the band’s eight members—Steve Cropper, Duck Dunn, Willie Hall, Tom Malone, Lou Marini, and Alan Rubin—were with Jake and Elwood since they formed the band in 1977. Five of the group–Steve Cropper, Donald “Duck” Dunn, Tom Malone, Lou Marini, and Alan Rubin—played with Levon Helm and the All-Stars on their first album and several concert dates. Willie Hall joined the group for Helm’s second album and the 1979 Japanese tour. Cropper, Dunn, and Hall had also worked together with Booker T. and the M.G.s and other artists at Stax Records. Tom Malone and Lou Marini first met as teenagers at the National Stage and Band Camps and later attended North Texas State University, where they played in the award-winning One O’clock Lab Band. They went on to work together in the Woody Herman touring band; Doc Severinsen’s orchestra; Blood, Sweat and Tears; and on Saturday Night Live. Malone, Marini, and Alan Rubin have also played together with Frank Zappa and The Band, and on Saturday Night Live.

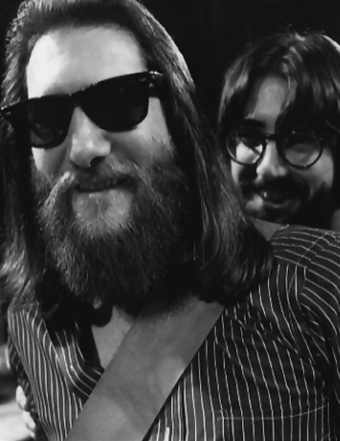

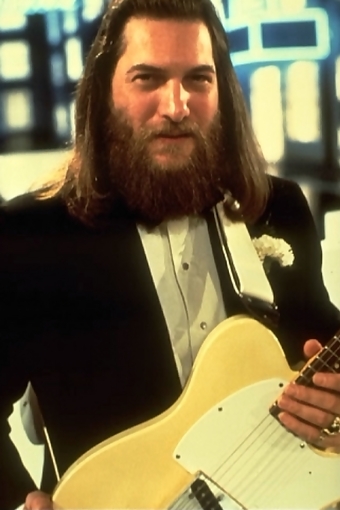

Steve Cropper (Lead Guitar) won a large following during his fertile ten years at Stax Records, where he was lead guitar for Booker T. and the M.G.s as well as performing and producing for various other artists. At Stax he was instrumental in developing the unique and popular “Memphis sound.” Records by Booker T. and the M.G.s that Cropper helped create include “Green Onions” and “Doin’ Our Thing,” Cropper, who had hundreds of BMI-registered songs recorded, co-wrote “Dock Of The Bay” “Fa-Fa-Fa,” and “Knock on Wood.” Cropper has produced records for Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, and Eddie Floyd, among others, and has accompanied them and other top artists, such as Rod Stewart, Art Garfunkel, Neil Sedaka, Rufus and Carla Thomas, Jerry Lee Lewis, Kenny Rankin, Levon Helm, Johnnie Taylor, Stephen Bishop, and Elvis Presley. His work at Stax also includes three Albert King albums “King Of The Blues Guitar,” “Years Gone By,” and “King Does The King’s Thing.” Cropper was born in Willow Springs, Missouri. In Memphis he and Duck Dunn formed the Mar-Keys band in their teens. Cropper recently signed a pact with MCA Records. Steve Cropper (Lead Guitar) won a large following during his fertile ten years at Stax Records, where he was lead guitar for Booker T. and the M.G.s as well as performing and producing for various other artists. At Stax he was instrumental in developing the unique and popular “Memphis sound.” Records by Booker T. and the M.G.s that Cropper helped create include “Green Onions” and “Doin’ Our Thing,” Cropper, who had hundreds of BMI-registered songs recorded, co-wrote “Dock Of The Bay” “Fa-Fa-Fa,” and “Knock on Wood.” Cropper has produced records for Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, and Eddie Floyd, among others, and has accompanied them and other top artists, such as Rod Stewart, Art Garfunkel, Neil Sedaka, Rufus and Carla Thomas, Jerry Lee Lewis, Kenny Rankin, Levon Helm, Johnnie Taylor, Stephen Bishop, and Elvis Presley. His work at Stax also includes three Albert King albums “King Of The Blues Guitar,” “Years Gone By,” and “King Does The King’s Thing.” Cropper was born in Willow Springs, Missouri. In Memphis he and Duck Dunn formed the Mar-Keys band in their teens. Cropper recently signed a pact with MCA Records.

|

|

| Steve Cropper on the set |

Steve Cropper publicity still |

Donald “Duck” Dunn (Bass Guitar) was the bass player for Booker T. and the M.G.s at Stax Records, where his many credits include “The Pinch,” “Lovejoy,” “Last Night,” “Doin’ Our Thing,” “McLemore Avenue,” “Booker T. And The M.G.s Greatest Hits,” “The Best of Booker T. And The M.G.s,” “Universal Language,” “Jammed Together,” and “Born Under A Bad Sign.” During this highly creative period at Stax he also played on three Albert King albums as well as accompanying such artists as Otis Redding, Sam and Dave, Wilson Pickett, Eddie Floyd, Rufus and Carla Thomas, and Johnnie Taylor. Most of this work was done with Steve Cropper. Their musical collaboration and friendship dateed back to their hometown of Memphis, where they were charter members of the Mar-Keys band. Other artists whom Dunn has accompanied include Muddy Waters, Levon Helm, Peter Frampton, Rod Stewart, Joan Baez, and Leon Russell

Donald “Duck” DunneMurphey Dunne (Keyboards) was born in Chicago. His film work included parts in Oh, God!, The Main Event, The Last Married Couple In America, and Mel Brooks’ High Anxiety and Silent Movie. Dunne scored the CBS-TV movie Outside Chance and the Academy Award-nominated short “Solly’s Diner.” Dunne, who has also acted on several television shows, was a veteran of Second City. He worked there as an actor and accompanist in Chicago and on tour, including “The Best Of Second City” revue at New York’s East Side Playhouse. He also appeared with the comedy groups The Committee, The National Theater of the Deranged, and The Celanese Players. Dunne was titular head of The Conception Corporation, where he wrote, produced, and performed on the group’s Atlantic record albums.

Donald “Duck” DunneMurphey Dunne (Keyboards) was born in Chicago. His film work included parts in Oh, God!, The Main Event, The Last Married Couple In America, and Mel Brooks’ High Anxiety and Silent Movie. Dunne scored the CBS-TV movie Outside Chance and the Academy Award-nominated short “Solly’s Diner.” Dunne, who has also acted on several television shows, was a veteran of Second City. He worked there as an actor and accompanist in Chicago and on tour, including “The Best Of Second City” revue at New York’s East Side Playhouse. He also appeared with the comedy groups The Committee, The National Theater of the Deranged, and The Celanese Players. Dunne was titular head of The Conception Corporation, where he wrote, produced, and performed on the group’s Atlantic record albums.

|

|

| Murphey Dunne on the set |

Murphey Dunne Publicity still |

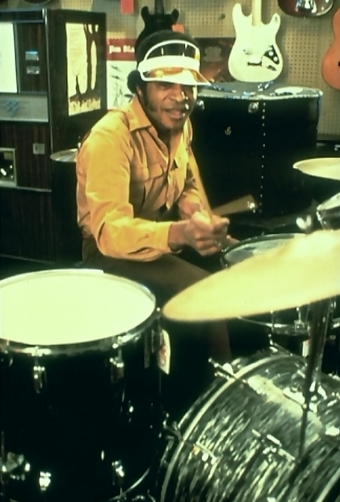

Willie Hall (Drums) was born in Jacksonville, and moved to Memphis in his teens. He began his career as a drummer in 1965, while still in high school. He played with the new Bar-Kays band, and later joined Stax Records, where he performed with Steve Cropper and Duck Dunn on Booker T. and the M.G.s’ records “Universal Language and “Hip Hug-Her.” Other Stax artists whom Hall accompanied and/or produced include The Emotions, Little Milton, Carla and Rufus Thomas, Johnnie Taylor, The Staple Singers, Albert King, Inez Fox, and Isaac Hayes. Hall produced Hayes’ last Stax album and later did percussion on Hayes’ popular “Shaft” album and Hayes’ Oscar-winning score for the hit film. Hall toured the world and recorded with a variety of artists, including Bonnie Raitt, Earl Scruggs, Charlie Daniels, Buffy Saint Marie, and Yvonne Elliman. Born in Jacksonville, he moved to Memphis in his teens.

|

|

| Willie Hall |

Willie Hall publicity photo |

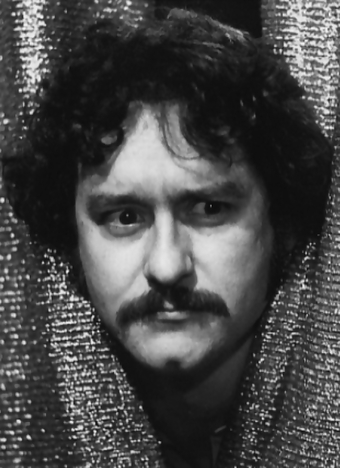

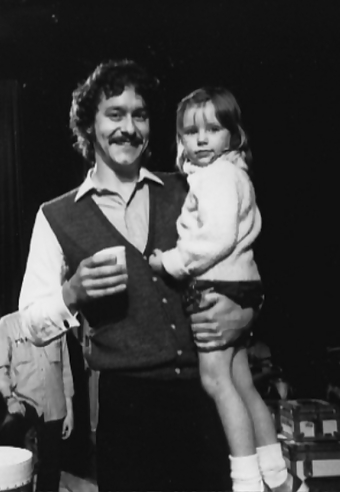

Tom Malone (Trombone, Tenor Sax) arranged for The Blues Brothers and for Saturday Night Live, where he has also played on various segments, including Gilda Radner’s “Candy Slice” numbers. Malone played horn and did arrangements for The Band in their 1974 summer tour and in Martin Scorcese’s film The Last Waltz. Malone’s many other musical credits include a year of tours and records with Blood, Sweat and Tears; U.S. and European tours with Frank Zappa’s band; touring with Doc Severinsen’s orchestra; playing with the New York group Ten Wheel Drive, Billy Cobham’s orchestra, and Levon Helm; and in the Waldorf-Astoria show band, for such acts as Peggy Lee, Jose Feliciano, Dionne Warwick, and Johnny Mathis. On records he has backed up such varied artists as James Brown, Spyro Gyra, Pink Floyd, Instant Funk, Stuff, and Vicky Sue Robinson. While studying for his BA in Psychology at North Texas State University, Honolulu-born Malone played in the award-winning One O’clock Lab Band and for various musical acts including Diana Ross, The Temptations, Stevie Wonder, Gladys Knight and the Pips, and the Tommy Dorsey and Woody Herman bands. Malone did horn arrangements for The Blues Brothers in the movie.

|

|

| Tom Malone Publicity Still |

Tom Malone on-set with his daughter |

Lou Marini (Saxophone) was born in Charleston, S.C. While studying Music Education at North Texas State University, he did Dallas studio work and Fairmont Hotel bookings for Ella Fitzgerald, Doc Severinsen Nancy Wilson, Diana Ross, and Gladys Knight and the Pips, and went on the road with the Woody Herman and Joe Morello bands. During this period, Marini was a member of the award-winning One O’clock Lab Band, with which he toured Mexico for the State Department and played the White House twice. He (Saxophone) received a grant for musical composition from the National Endowment for the Arts. He was also commissioned by the Symphonia Foundation to compose a jazz choral piece for 20 male voices and jazz band, which he conducted in 16 engagements around the U.S. With the Bowling Green State University Symphony, he conducted three experimental pieces for orchestra and jazz soloists. To work in The Blues Brothers movie, Marini took a leave from Saturday Night Live, where he had been a sax soloist for four years. For two years he was sax soloist with Blood, Sweat and Tears, for whom he also composed and arranged. He has done studio session work for such performers as Frank Zappa, The Band, Crystal Gayle, and Aerosmith. His concert backup work includes such diverse attractions as Ella Fitzgerald, Manhattan Transfer, John Tropez, Levon Helm, The Joffrey Ballet, the Alvin Ailey Dance Company, and a Canadian tour of The Bee Gees. Marini also played for Doc Severinsen’s band on The Tonight Show; arranged for Buddy Rich and played on the movie scores of Hair, The Wiz and The Last Waltz. Marini later taught for four summers at the National Stage and Band Camps, which he attended as a teenager.

|

|

| Lou Marini on the set |

Lou Marini publicity still |

Matt Murphey (Guitar) met John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd during his six years with the James Cotton Blues Band. Among his many other music credits, Murphy did extensive session work at Chess Records with artists like Sonny Boy Winson, Muddy Waters, Chuck Berry, Little Brother Montgomery, and Little Junior Parker. Born in Sunflower, Mississippi, Murphy played in Memphis with Memphis Slim and The House Pickers, Jack McDuff’s organ trio, and others. Memphis Slim urged him to go to Chicago in his early twenties, where he studied jazz under Reggie Boyd.

|

|

| Matt Murphey smiles for the publicity camera |

Matt Murphey |

Alan Rubin (Trumpet) was a scholarship student at the Julliard School of Music, where he studied trumpet under William Vacchiano (former solo trumpet with the New York Philharmonic) and played in the Julliard Orchestra. In his teens he was solo trumpet with the New York All-City High School Orchestra and with the Newport Youth Band. With the latter group he recorded “Live at the Newport Jazz Festival.” In his late teens, Rubin spent summers playing in hotel bands in the Catskills. At 20, he was the lead trumpet for concerts and tours of Robert Goulet and Jack Jones. Now one of the top trumpet players in his native New York, Rubin was the trumpet player on Saturday Night Live for four years, from its inception. He has also played for Frank Zappa, The Band, a five-concert Frank Sinatra tour, and for Carol Lawrence at the Red Cross benefit in Monaco. Among Rubin’s extensive recording work, he played with such artists as The Rolling Stones, Blood, Sweat and Tears, Burt Bacharach, and Duke Ellington, and was lead trumpet on Meco’s hit Star Wars album, in which the 45rpm single jumped to the top spot on Billboard’s charts.

Alan Rubin

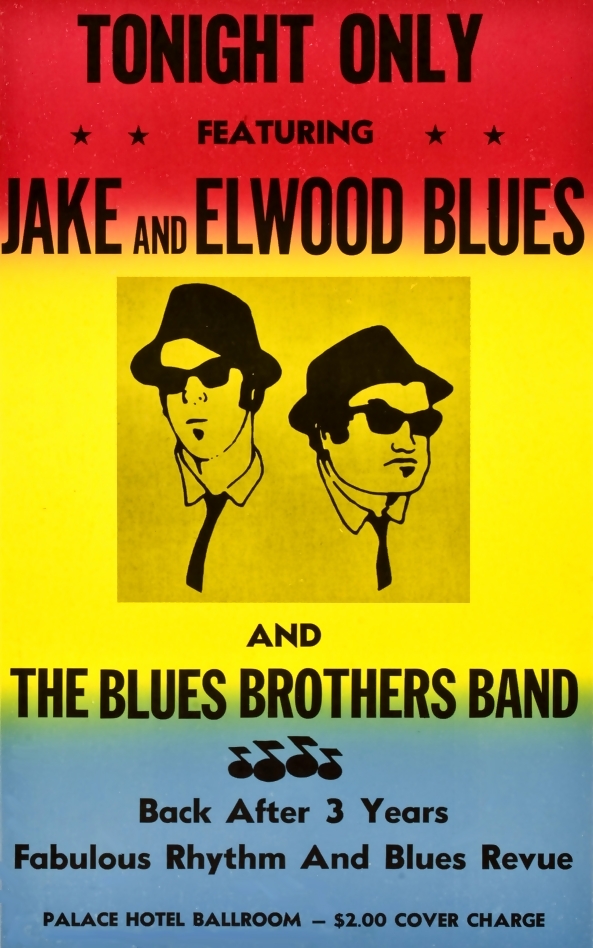

Alan Rubin You might recognize this poster, handed out in the film to promote the fund-raising concert.John Belushi

You might recognize this poster, handed out in the film to promote the fund-raising concert.John Belushi

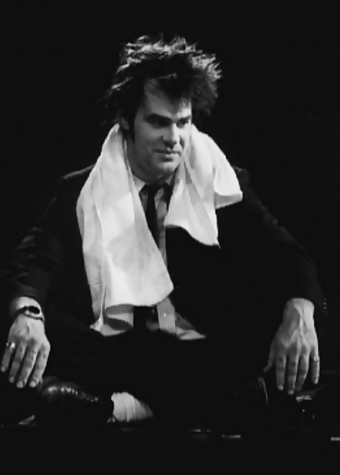

John Belushi was born in Chicago, where the film takes place. He was one of the original cast members of NBC’s Saturday Night Live in its golden years. In 1934, his parents had migrated to the United States from Qyteze, Albania. He was the older of two children, his brother is Jim Belushi, still working in film. He was raised near Chicago in Wheaton, Illinois. Following high school, he decided he wanted to be in comedy and got a break with The Second City Comedy Club in Chicago. In 1973, he felt that Chicago would not get him where he wanted to be as far as a career in entertainment, so he moved to New York, He then went on to work for National Lampoon on several of their albums and stage shows. He was noticed in his live shows and was hired for Saturday Night Live in 1975. Soon after that he was cast in National Lampoon’s Animal House which brought him immediate fame. He decided that California was now going to be his base and within several weeks he was a new resident of California.

Belushi and Aykroyd with then Chicago Mayor Jane ByrneJohn loved blues music, and in large part this is how The Blues Brothers came about. He then went on to film Continental Divide and also took some cameos in television series such as Police Squad. At the end of his life, he lived at the Chateaus Marmont in Hollywood. He was found dead on March 5, 1982 at the age of 33. in his apartment. John had taken a “speedball,” which is a mix of cocaine and heroin. It was officially ruled as an accident, though some question what might have happened in the hotel room that night. His legacy lives on. For more information on John Belushi, see my recent column on Animal House here

Belushi and Aykroyd with then Chicago Mayor Jane ByrneJohn loved blues music, and in large part this is how The Blues Brothers came about. He then went on to film Continental Divide and also took some cameos in television series such as Police Squad. At the end of his life, he lived at the Chateaus Marmont in Hollywood. He was found dead on March 5, 1982 at the age of 33. in his apartment. John had taken a “speedball,” which is a mix of cocaine and heroin. It was officially ruled as an accident, though some question what might have happened in the hotel room that night. His legacy lives on. For more information on John Belushi, see my recent column on Animal House here

Dan Aykroyd Dan Aykroyd

In the film, Dan Aykroyd wears, as they say in showbiz, two hats, both black “skinny brims.” In this large-scale musical comedy the versatile Canadian achieves a double triumph. As actors, he and co-star John Belush brought to the screen their popular musical creations, Jake and Elwood Blues. Also, the original script marked the screen-writing debut of Aykroyd, who holds an Emmy for his writing on the innovative Saturday Night Live television show. Aykroyd, who wrote The Blues Brothers with director John Landis, described the movie as “a Christian crusader’s tale, a simple story of good and evil with no hidden meanings or messages He describes Elwood and himself as “a motor head.” The film gave Aykroyd an opportunity to indulge his love of cars and mechanics, which dated from early childhood. His first car was a 1939 Dodge which his father bought for him for $125 in Hull (Quebec). The vehicle had been painted black with a broom. Aykroyd repainted it and used it for a year at Carlton College, in his home town of Ottawa. He graduated at 20 and pursued various work such as truck-driving, criminology, and operating a bar.

|

|

| Make-up for Dan Aykroyd |

Rare shot of Aykroyd relaxing on the set |

He auditioned for and won a role in the Toronto company of the renowned improvisational comedy group Second City. From his work there and at the Pasadena Playhouse, he was asked to join “the killer elite of comedy” on Saturday Night Live. He was a member of the “Not Ready For Prime Time Players” and starred on the show for five historic seasons. He created an astounding variety of comic characters including the father of the Conehead family, one of the “swinging” Czecho-slavakian Festrunk brothers, a German Superman, and his incisive impersonations of President Carter and Tom Snyder. Out of their lifelong passion for rhythm and blues, Aykroyd and Saturday Night Live co-star Belushi created The Blues Brothers and gathered the back-up band. They performed the act on a few Saturday Night Live warm-ups and then twice on the show in 1977-78. Then came their thunderously received appearance with Steve Martin at the Universal Amphitheatre in Los Angeles in June of 1978. Their first Atlantic album, “A Briefcase Full of Blues,” sold over two and-a-half million units, was nominated for three Grammy Awards, and started a revival of rhythm and blues music. The Blues Brothers subsequently performed at Carnegie Hall; the closing show at Winterland in San Francisco on New Year’s Eve, 1978; and at the ChicagoFest summer music festival just prior to the Chicago-location filming.

(l-r) John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd on the set

(l-r) John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd on the set Publicity still of (l-r) John Belushi and Dan AykroydJames Brown

Publicity still of (l-r) John Belushi and Dan AykroydJames Brown

I was raised in the church. Everybody always said I’d grow up to be a minister,” said singer-dancer James Brown who plays a fiery preacher. Brown stars as the Reverend Cleophus James, who helps generate some divine inspiration for Jake and Elwood when they visit the Triple Rock Baptist Church. Brown delivers a sermon, sings the gospel song “The Old Landmark,” and sets the Chicago congregation dancing in the aisles.

(l-r) James Brown and Director John Landis on the setBefore becoming the highly-charged musical performer Reader’s Digest called “Soul Brother No.1,” James Brown sang in church choirs for two-and-a-half years. He toured with the Reverend Willingham’s Sewanee Quintet and recorded an album with James Cleveland’s choir, the gospel group that backs him up in his revival number in The Blues Brothers. Gutsy, flamboyant Brown is called “Mister Dynamite” and “The Godfather of Soul.” His international musical success became a symbol of hope, courage, and upward mobility for African American people everywhere. A Newsweek article observed: “Who speaks for the black man in the streets? Above all, the soul singer, James Brown. In his career, James Brown had over one hundred songs on the charts including over 50 gold records. His hits incline “Bewildered,1 “It’s A Man’s World,” “Say It Loud, I’m Black And Proud,” “Prisoner Of Love,” “Sex Machine,” “Cold Sweat,” “Give It Up Or Turn It Loose,” and “Get On The Good Foot.” He won a Grammy Award for Best Rhythm and Blues male vocal of 1965 for “Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag,” the smash hit that first brought Brown’s talent to white audiences. Among Brown’s many hit albums, “Alive At The Apollo” established a record by staying on the Billboard chart for 66 consecutive weeks.

(l-r) James Brown and Director John Landis on the setBefore becoming the highly-charged musical performer Reader’s Digest called “Soul Brother No.1,” James Brown sang in church choirs for two-and-a-half years. He toured with the Reverend Willingham’s Sewanee Quintet and recorded an album with James Cleveland’s choir, the gospel group that backs him up in his revival number in The Blues Brothers. Gutsy, flamboyant Brown is called “Mister Dynamite” and “The Godfather of Soul.” His international musical success became a symbol of hope, courage, and upward mobility for African American people everywhere. A Newsweek article observed: “Who speaks for the black man in the streets? Above all, the soul singer, James Brown. In his career, James Brown had over one hundred songs on the charts including over 50 gold records. His hits incline “Bewildered,1 “It’s A Man’s World,” “Say It Loud, I’m Black And Proud,” “Prisoner Of Love,” “Sex Machine,” “Cold Sweat,” “Give It Up Or Turn It Loose,” and “Get On The Good Foot.” He won a Grammy Award for Best Rhythm and Blues male vocal of 1965 for “Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag,” the smash hit that first brought Brown’s talent to white audiences. Among Brown’s many hit albums, “Alive At The Apollo” established a record by staying on the Billboard chart for 66 consecutive weeks.

Brown was born in the “poor black country” of Augusta, Georgia where his father greased and washed cars for a filling station. “My family was so poor you wouldn’t believe it,” recalls Brown. “Sometimes I worked for my father, other times I picked cotton or worked in a coal yard. In the afternoons I had to walk home along the railroad tracks and pick up pieces of coal left over from the trains. I’d take them home and we’d use them to keep warm.” To raise money for class projects James entertained the kids at school, who paid a dime to see him perform. “I always loved to dance, even when I was eight years old,” said Brown. “I’d dance for the National Guard soldiers from Fort Gordon who were camped outside, and they’d throw nickels, dimes, sometimes quarters, at me. I took them home to help my folks pay the rent.” James left school in the seventh grade. After picking cotton, shining shoes, and boxing, he ended up in reform school for breaking and entering an automobile with several other youths. Sentenced to a term of from eight to sixteen years, he was a model prisoner.

He petitioned the parole board on his own behalf and was released after three years. He channeled his energies into music and church work. While working as a school janitor, he formed his own musical group. In 1956, James Brown and the Famous Flames cut a record for a Macon, Georgia radio station which attracted the attention of Sid Nathan, owner and founder of King Records. The song was Brown’s first hit, “Please, Please, Please,” which launched him into stardom. In 1971 Nathan died and Brown signed with Polydor Records. His albums include two volumes of “Soul Classics,” “Revolution Of The Mind,” “Get On The Good Foot,” “Disco Man,” and “Future Shock.” Brown had his own label, People Records, within the Polydor organization. He was a pioneer of extended tours for black artists and was the first soul singer to play the Grand Ole Opry. He wrote the scores for the films “Black Caesar” and “Slaughter’s Big Rip-Off.” He was the first American entertainer to receive the Order of the Star from the President of Liberia. Brown’s business domain included a music publishing firm, three radio stations, and extensive real estate holdings. He also found time for humanitarian activities such as drug rehabilitation, civil rights, and job opportunity programs. He also authored the book “Don’t Be A Dropout.”

Aretha Franklin Aretha Franklin

“Soulful and strong” is the way Aretha Franklin described the woman she plays in the film. The description applies equally to the hot-tempered cafe owner she portrays and to her own historic career as a vocalist. The powerful and popular singer, internationally known as “The Queen of Soul,” is the holder of ten Grammies, seven gold albums, and 14 gold singles, including “Think!,” which she co-wrote and reprised in a full-scale production number, a highlight of The Blues Brothers. “Music has always been my thing,” says Aretha. Her success story started in gospel choirs in Detroit, where she moved at age two with her family from her birthplace of Memphis, Tennessee. One of five children of the Rev. C. L. Franklin, she acquired her early training as a singer with her brothers and sisters in the pastorate choir of her father’s 4500-member New Bethel Baptist Church.

Guided by jazz bass player Major “Mule” Holly, at 18 Aretha decided to try for a career as a blues singer. At Holly’s suggestion, and encouraged by her father, Aretha went to New York and auditioned for Columbia Records A&R chief John Hammond (whose previous discoveries included Billie Holiday, Count Basie, and Bob Dylan). He signed her on the spot. During this period some of Aretha’s songs made the charts and she gained notice among blues, jazz and soul music fans. Then she switched to the Atlantic label in 1966. Her personal manager Jerry Wexler teamed her with new musicians and new tunes and catalyzed the thrilling style which The Rock Encyclopedia later referred to as “the epitome of unleashed female passion.” Music historian Tony Heilbut quoted Wexler as saying, “I took her to church, sat her down at the piano, and let her be herself.” The first flowering of this new phase of Aretha’s talent was the single “I Never Loved A Man (The Way I Love You),” an overnight smash and Aretha’s first gold record. The album of the same title also went gold and contained the classic “Respect,” subsequently released as a gold single. With the gold single “Baby, I Love You” and the hit album “Aretha Arrives,” she was established as the reigning new star of rock and soul music. Producer Jon Landau’s prophetic liner-notes to Aretha’s next gold album, “Aretha: Lady Soul,” observed that the emergence of blues into pop music during 1967, epitomized by Aretha’s successes, would continue its surge into 1968.

Aretha Franklin discussing the sceneHe referred to 1967 as “the year in which rhythm and blues became the music of the charts and the year in which soul became the popular music of America.” The release of “Lady Soul” in January, 1968, followed on the success of one of its great single tracks, “(You Make Me Peel Like) A Natural Woman,” The album also included Aretha’s next pair of gold singles, “Chain Of Fools” and “Since You’ve Been Gone” which made her the first woman in RIAA history to earn five certified gold singles. That year she walked away with NATRA’s coveted award as “Singer of the Year.” She swept the trade magazine polls—Billboard, Cash-box, and Record World—in both singles and album categories. And she earned two Grammys for “Best Rhythm and Blues Recording (“Respect”) and “Best Female Rhythm and Blues Singer of the Year.”

Aretha Franklin discussing the sceneHe referred to 1967 as “the year in which rhythm and blues became the music of the charts and the year in which soul became the popular music of America.” The release of “Lady Soul” in January, 1968, followed on the success of one of its great single tracks, “(You Make Me Peel Like) A Natural Woman,” The album also included Aretha’s next pair of gold singles, “Chain Of Fools” and “Since You’ve Been Gone” which made her the first woman in RIAA history to earn five certified gold singles. That year she walked away with NATRA’s coveted award as “Singer of the Year.” She swept the trade magazine polls—Billboard, Cash-box, and Record World—in both singles and album categories. And she earned two Grammys for “Best Rhythm and Blues Recording (“Respect”) and “Best Female Rhythm and Blues Singer of the Year.”

Aretha Franklin photo shot by a cast memberThe same year the film was shot, Aretha accepted a long-standing invitation to tour Europe, a two-week stay that took her to seven major cities in England, France, Germany, Holland, and Sweden for concert and television appearances. Her concert at the Olympia Theater in Paris was recorded and later released (October) as Aretha In Paris. On the last Friday in February, 1969, Aretha gave her triumphant concert at Cobo Hall in Detroit. Mayor Cavanaugh issued a proclamation declaring that date “Aretha Franklin Day,” and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. flew up from Atlanta to present Aretha with a special award from the Southern Christian Leadership Council. In 1970, 1971, and 1972 Aretha again captured Grammies for “Best Female Rhythm and Blues Singer of the Year,” on the strength of four more consecutively-released gold singles. Her albums kept up the pace as well, “Live At Fillmore West” (her first live album since “Paris”), “Young Gifted, and Black,” and then “Amazing Grace” (filmed and recorded live with Rev. James Cleveland’s Southern California Community Choir of the New Temple Missionary Baptist Church fin Los Angeles, and released as Aretha’s first double-LP). All three were certified gold, bringing Aretha’s track record to a staggering total of six gold albums and thirteen gold singles.

Aretha Franklin photo shot by a cast memberThe same year the film was shot, Aretha accepted a long-standing invitation to tour Europe, a two-week stay that took her to seven major cities in England, France, Germany, Holland, and Sweden for concert and television appearances. Her concert at the Olympia Theater in Paris was recorded and later released (October) as Aretha In Paris. On the last Friday in February, 1969, Aretha gave her triumphant concert at Cobo Hall in Detroit. Mayor Cavanaugh issued a proclamation declaring that date “Aretha Franklin Day,” and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. flew up from Atlanta to present Aretha with a special award from the Southern Christian Leadership Council. In 1970, 1971, and 1972 Aretha again captured Grammies for “Best Female Rhythm and Blues Singer of the Year,” on the strength of four more consecutively-released gold singles. Her albums kept up the pace as well, “Live At Fillmore West” (her first live album since “Paris”), “Young Gifted, and Black,” and then “Amazing Grace” (filmed and recorded live with Rev. James Cleveland’s Southern California Community Choir of the New Temple Missionary Baptist Church fin Los Angeles, and released as Aretha’s first double-LP). All three were certified gold, bringing Aretha’s track record to a staggering total of six gold albums and thirteen gold singles.

Aretha celebrated her tenth anniversary on Atlantic with the release of Sparkle, music from the Warner Brothers motion picture, composed and produced by Curtis Mayfield, their first collaboration. The album’s initial single “Seething He Can Feel” was released on May 5 (two weeks ahead of the album), shot straight up to the #1 slot on the Billboard, Cashbox, and Record World R&B charts and hung around the top ten until the summer was over. The Sparkle album itself was certified gold during 4th of July week, her 21st gold record. It coincided with the news that she’d been nominated as “Best Female Vocalist of the Year” for Don Krishner’s Rock Awards telecast. In 1980 Aretha switched to the Arista label, where she continued to produce hit songs on the Easy Listening and soul charts.

Ray Charles Ray Charles

In “The Blues Brothers,” Ray Charles plays a crafty music store owner to whom Jake and Elwood Blues (John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd) come to get instruments for the most important gig of their lives. “I know how it can be when a musician needs an instrument,” said Charles. For this showman, the role recalled his own courageous struggle to become a musician. “I remember pinching pennies and denying myself to save enough money for the first instrument I ever owned, a sax,” said Ray. “I got it in a music store in Atlanta, and I had to horse-trade with the cat just like these guys.” Ray Charles is internationally acclaimed as a musical genius whose inspiring talent embraces jazz, blues, pop, soul, and even country-western. Charles’ work has been honored with platinum albums, gold singles, and over ten Grammy Awards. He is in Playboy magazine’s Jazz and Pop Hall of Fame, and the Songwriters’ Hall of Fame, among other international tributes. In 1979, his version of “Georgia On My Mind” was made the official state song of Georgia.

Ray got his first introduction to music at age four at the upright piano of a neighbor in his hometown of Albany, Georgia. “There was an old gentleman named Wiley Pittman, and he had his old beat-up piano on the front porch. I’d go over and stand by the piano and listen, and pretty soon he’d move over and make room for me and I’d sit down and bang away up on the high keys but I wasn’t playing anything. He knew it, but he’d smile and say, “That’s good, that’s so good sonny. But you gotta practice.” Ray’s father (Bailey Robinson) worked as a handyman, and his mother, (Aretha) took in washing. The family was poor but full of love and hope. The first personal tragedy young Ray had to overcome was the death of his younger brother George, who accidentally drowned in a washtub in the front yard before panic-stricken Ray could summon his mother. When Ray was six, the family moved to Greenville, Florida. Here Ray contracted his blindness, which doctors assume was a variety of glaucoma. Much of the courage with which he fought back was derived from his mother, who told him, “You’re blind, not stupid. You’ve lost your sight, not your mind.” Ray’s father died when the boy was ten, and his mother passed on five years later. Ray went to live at St. Augustine’s School for the Deaf and Blind in Orlando, Florida. Here the teenage musician got the instruments he craved, but only after “a lot of perseverance” by him and his teacher, Mrs. Lawrence Garrett Grant.

Dan Aykroyd, Ray Charles and John Belushi publicity still“Even in a place full of blind people there was segregation,” recalled Charles. “And the instruments went to the white children first.” But thanks to his determined teacher, Ray got to study piano and clarinet and was given the extraordinary privilege of taking the clarinet home for the summer to Gainesville, Georgia. Still in his teens and refusing to be stopped by his handicap, Charles left St. Augustine’s to join a dance band in Jacksonville. He toured with the group throughout Florida and Georgia and got his union card by lying about his age. Anxious to get away from the South, Charles went by bus to Seattle. He heard about a talent contest at a club called The Rockin’ Chair and talked his way in. He didn’t win but did get job offers at the Rockin’ Chair and the Seattle Elks Club. People told him he sounded like Nat “King” Cole. “I wanted to make money, so I tried to copy Cole and Charles Brown. But it wasn’t the real me. I was just pretending. Finally I said to myself ‘From now on, win, lose, or draw, they’re going to have to accept me for the way I sound myself.’ He was approached by a Los Angeles record company and cut “Confession Blues.” But the striking musicians’ union had banned recording, and Charles was fined $600. He continued to develop his own style during a year on the road with Lowell Fulsom’s blues band. Charles’ mixture of gospel and blues earned him an underground following among African American audiences.

Dan Aykroyd, Ray Charles and John Belushi publicity still“Even in a place full of blind people there was segregation,” recalled Charles. “And the instruments went to the white children first.” But thanks to his determined teacher, Ray got to study piano and clarinet and was given the extraordinary privilege of taking the clarinet home for the summer to Gainesville, Georgia. Still in his teens and refusing to be stopped by his handicap, Charles left St. Augustine’s to join a dance band in Jacksonville. He toured with the group throughout Florida and Georgia and got his union card by lying about his age. Anxious to get away from the South, Charles went by bus to Seattle. He heard about a talent contest at a club called The Rockin’ Chair and talked his way in. He didn’t win but did get job offers at the Rockin’ Chair and the Seattle Elks Club. People told him he sounded like Nat “King” Cole. “I wanted to make money, so I tried to copy Cole and Charles Brown. But it wasn’t the real me. I was just pretending. Finally I said to myself ‘From now on, win, lose, or draw, they’re going to have to accept me for the way I sound myself.’ He was approached by a Los Angeles record company and cut “Confession Blues.” But the striking musicians’ union had banned recording, and Charles was fined $600. He continued to develop his own style during a year on the road with Lowell Fulsom’s blues band. Charles’ mixture of gospel and blues earned him an underground following among African American audiences.

Charles then formed a group to accompany singer Ruth Brown, and on his own he played the Apollo in Harlem. He returned to Seattle, and became the leader of the Maxim trio, the first Negro act to have a sponsored television show in the Pacific Northwest. He recorded for a small label called Swingtime, and then, in 1954, Atlantic bought his contract. By now Charles was a perfectionist musician and tired of the eccentricities of house bands: “I’d find two horns one night and six the next. And they were always lousy.” So Charles formed his own seven-piece group and told Atlantic he was ready to record. From that session emerged “I Got A Woman.” This hit introduced Ray Charles to white audiences and began his immense success as a cross-over attraction. In 1959 Charles switched to the ABC Records label where he remained until 1973. He also recorded during this period for his own Tangerine label, which was distributed by ABC/Dunhill. He rejoined Atlantic, where his hit albums included “True To Live,” “Love And Peace,” and “Ain’t It So.” In 1973 Larry Newton, who had been associated with Ray at ABC/Dunhill, formed Crossover and Charles signed an exclusive deal with that label. Ray Charles’ frank autobiography (co-written with David Ritz) is called “Brother Ray.” Charles’ related activities include touring with the Ray Charles Revue; RPM International, the corporation which housed the West Coast offices of Crossover Records; Charles’ music publishing companies, Tangerine and Racer Music; and RPM recording studios.

In addition to his music, Charles remained an inspiration because of the extraordinary courage and good humor with which he has confronted his blindness. “Seeing or not seeing, life is still life,” he has said. “People should never be bitter about anything. They should go out into the world and learn to keep fighting for themselves.” In his spare time, Charles enjoys building and repairing mechanical equipment such as television sets, record players, and even his company planes. Charles, his wife Delia, and their three sons—Ray Jr., David, and Robert—made their home in Los Angeles.

Cab Calloway Cab Calloway